Dear Andy Warhol Puzzle I Cannot Name,

Please don't be angry with me baby, but no ... No, I have not worked you and probably never will.

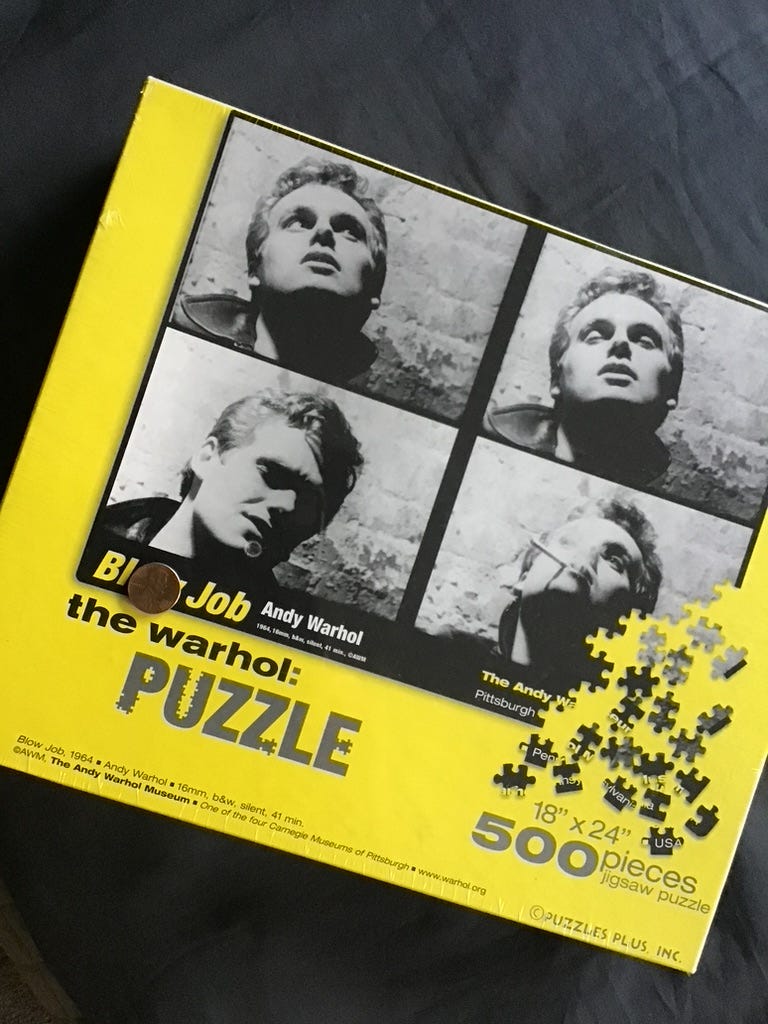

Go ahead and mock me from your place on my office bookshelf. You're nestled there between the 1000-piece Archibald Motley "Nightlife" (1943) and the 1000-piece Salvador Dali "Soft Watch at the Moment of its First Explosion" (1954). Lofty neighbors indeed, but you represent the human condition with the best of 'em, maybe more so. Some might see you as nothing more than a fragmented piece of cardboard, but I recognize your true greatness.

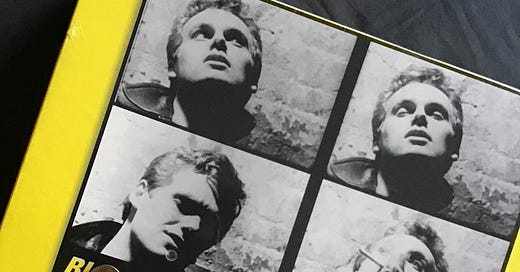

I understand you: What you are and where you come from and perhaps most importantly, what you want to be. Your history is unlike any other puzzle I know (and baby, I know A LOT about puzzles). You're simple enough in content, with just four black and white photographs of a DeVeren Bookwalter as he gazes, dreams, gently grimaces, and smokes. They're excised from a 41-minute film with which you share a name. But sitting there in your loud yellow box with the sensual images and the naughty title, you may not realize that the blessed event that established your existence was not 41 minutes in length, but only about 27. That's because back in 1964, your creator—one Andy Warhol—insisted on showing the film at a speed of 16 frames per minute even though he filmed it at 24. Warhol did many things with film, and with this one, he wanted to extend Bookwalter's delicious anguish and pleasure.

How brilliant is that?

And then there's you, taking it to the next level and beyond. You slow this quasi act of fellatio to the hours it would take to properly construct your 500 pieces, not to mention the days, weeks, and even years you've spent on a dusty closet shelf or buried in a rummage bin just waiting to be plucked from between the old purses and crushed Monopoly boxes. Only then can you realize your true glory, but of course, that would mean tearing off your shrink wrap and removing the bloom from your (ahem) rose.

Every hear of a purity ring? Oh hell … never mind.

Is a blow job really a blow job if it never comes to fruition? The question is at once impossible and facile; I have no idea how to answer it. And frankly, Andy Warhol Puzzle I Cannot Name, neither do you. We see what we see on your box and in the associated film, but other than an evocative title, we have no idea what Bookwalter is experiencing. He might have been alone in a room with a camera, acting the part.

Blow.

Job.

Oh my, how two little words can bend our fragile human minds. Language is powerful.

Way back in 2006 before I knew anything about you, I ran across Beautiful Agony, a site I once described thusly for the now-defunct Cleveland Free Times:

The subtitle of the site is "Facettes de la Petit Mort," or "Faces of the Little Death," the French euphemism for orgasm. This site features regular people doing what they have been doing (ahem) alone ever since they figured out how.

There is no nudity on the site. The available film clips feature men and women pictured from the shoulders up as they masturbate. The result is banal, fascinating, crass, embarrassing, beautiful, arousing and nerve-racking all at once. In me, the clips evoked a strange self-awareness.

It is entirely too human to be called pornography.

See?

Beautiful Agony is sort of like a democratic Blow Job movie that's been modernized for the internet and disseminated for the masses to enjoy. Granted, we're to assume the featured parties are engaging in self-pleasure instead of receiving oral ministrations. So what? The idea is the same and you and Warhol were there first.

I never saw the infamous Pamela Anderson sex tape, but a soundbite commentary about it referenced Pamela moving the camera from Tommy's member to his face just as he is about to climax. Did Anderson know anything about Warhol's film? Probably not, but she was doing precisely what a woman in love and lust would do: focusing on the nexus of sex. Genitals might handle the business end of the deal, but it's our eyes and gasps and distorted expressions that belie how we succumb to animal pleasure. To it, we relinquish control if only for a handful of moments (or a handful multiplied by 1.5 if Warhol's at the helm).

Further reading: Finding Warhol: Resurrecting a Lost Film

Warhol was 58 when he died in February 1987. Bookwalter died of stomach cancer in July of that same year. He was 47. They are gone; you are not. For the time being you sit there, Andy Warhol Puzzle I Cannot Name, a humble collection of weirdly shaped cardboard bits, fragmented yet intact behind a thin film of shrink wrap.

And now by the power vested in me, I shall write myself into your story. You will wait for your climax for 27 minutes and then for 41 minutes and then for a few hours and then for a whole year and for another year after that and another and another until I die.

Baby … this here? What we're doing? You and me? It's performance art.

There, there. Don't cry. I apologize for not realizing your full potential, but how else can I preserve you? So welcome to the land of purity, unconsummated love, and endless virginity.

Love, Erin

ps: I'm referring to you as the “Andy Warhol Puzzle I Cannot Name” on account of the ongoing censorial sweep across America, which frankly, seems like a fitting component to your story.

pss: The Andy Warhol collective to which you belong continues to dog we humans, all the way up to the highest court in the land.

If there were a test question — “Name a writer who could do an essay about strangely shaped bits of cardboard and relate it to oral sex” — there could be only one answer.

I love your writing, and someone capable of writing news like the best wire service reporter (as I noted about you some months back) and also of writing essays of surpassing weirdness has a rare talent.

Fine essay, this.