A few weeks ago, a friend handed me this kids' puzzle amid a pile of cast-offs. It came with an unspoken implication to which I've become accustomed: Erin is The Puzzle Lady. She'll know what to do with this.

Mostly I felt sorry for the kid who undoubtedly got this as a gift from an ancient aunt or uncle. “World geography is important!” was the likely accompanying advice, delivered along with the stern shake of a gnarled finger. Then little Sal or Chris or Malcolm tried to act grateful and hide their disappointment: It’s worse than a package of socks.

Feeling much like that kid, I pushed the box aside. It didn't take long, however, for my curiosity to get the best of me. (Is it complete?) Those big pieces came together in a snap.

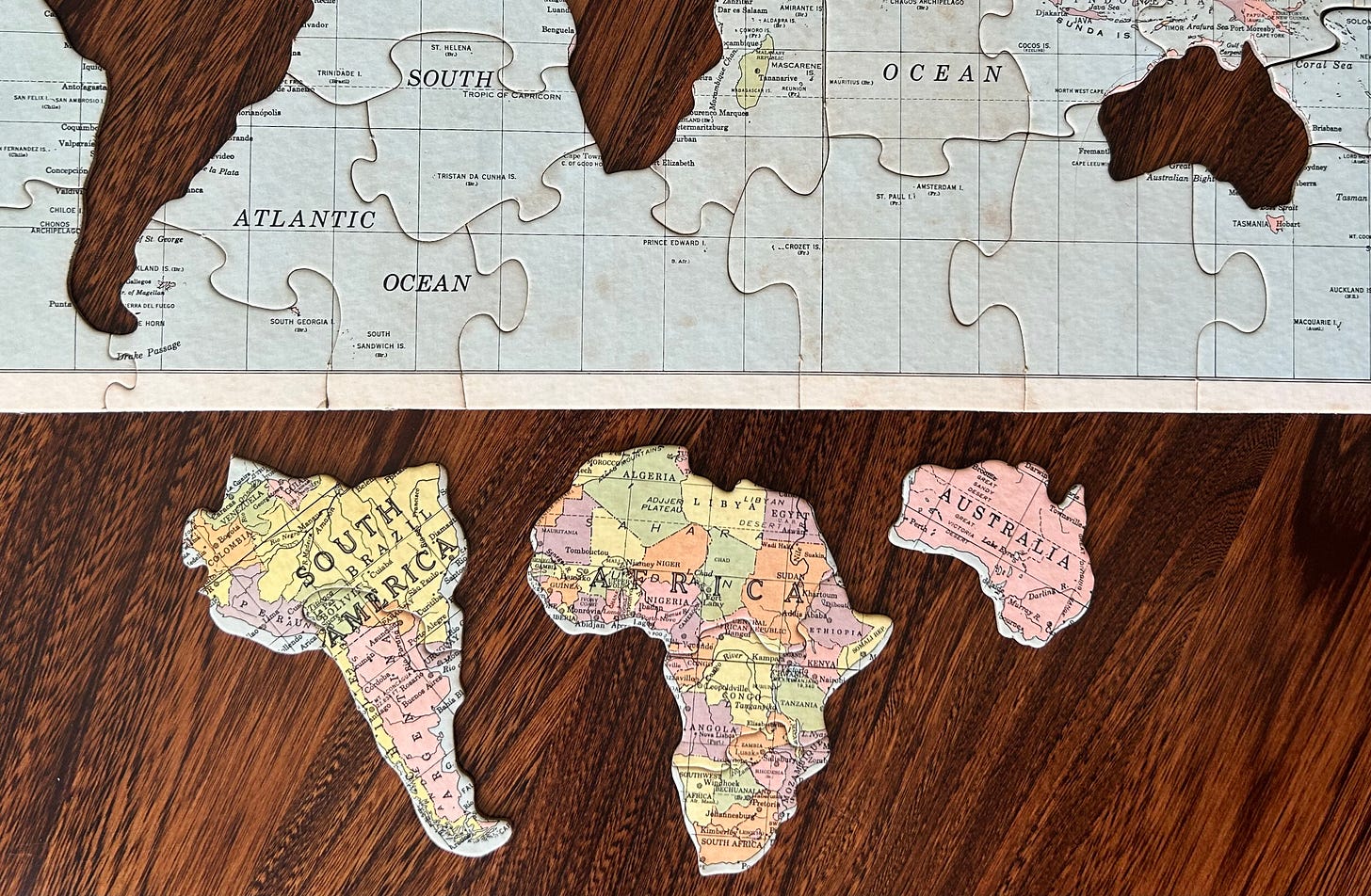

This puzzle is beautifully constructed, which is endearing and then some. The good people over at Selchow & Righter cared about junior puzzle-doers. The board is thick and strong—built to last. The image adhesion is as good as it gets; no peeling tabs or edges here. And when I saw Australia was its own piece and shaped accordingly, my opinion of this old puzzle further improved. Africa and South America were properly shaped as well. Someone in product development clearly tried to give this dud some zip. Good on 'em, but still … a standard map puzzle is just plain dreary. I sighed, then looked for a date. Nope. So what? The map would date itself.

This, friend, is when things started to get complicated.

It is so complicated, in fact, that it begins with a short story I first read more than 20 years ago.

The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien (no relation) details objects American soldiers stowed on their persons in the Vietnam War. It is the finest short story I have ever read. An excerpt:

The things they carried were largely determined by necessity. Among the necessities or near-necessities were P-38 can openers, pocket knives, heat tabs, wristwatches, dog tags, mosquito repellent, chewing gum, candy, cigarettes, salt tablets, packets of Kool-Aid, lighters, matches, sewing kits, Military Payment Certificates, C rations, and two or three canteens of water. Together, these items weighed between 15 and 20 pounds, depending upon a man's habits or rate of metabolism. Henry Dobbins, who was a big man, carried extra rations; he was especially fond of canned peaches in heavy syrup over pound cake. Dave Jensen, who practiced field hygiene, carried a toothbrush, dental floss, and several hotel-sized bars of soap he'd stolen on R&R in Sydney, Australia. Ted Lavender, who was scared, carried tranquilizers until he was shot in the head outside the village of Than Khe in mid-April. By necessity, and because it was SOP, they all carried steel helmets that weighed 5 pounds including the liner and camouflage cover. They carried the standard fatigue jackets and trousers. Very few carried underwear.

We modern Americans digest war from the comfort of our living rooms after the messy conflict has been reduced in size and content to fit on a screen. It is, at the very least, a sanitized experience. But when O'Brien tacks a packet of Kool-Aid right in the middle of it, we can see how massive and monstrous that war truly is.

The Kool-Aid gives us a reference. It provides scale, much like any known object—take a photo of a rock and no one will know if it’s as big as a mailbox or a house unless there’s someone standing next to it. The puzzle map provides reference as well, but in this case, it scales the size of our current troubles, how deep they run, and how very close they are.

The map contains copious evidence of how we grapple with our confounding environment. Just look at the orderly longitudinal and latitudinal lines. Or how we’ve found the center of it all and cleverly named it ‘the equator.’ We’ve even used rivers and oceans and mountains to separate one chunk of dirt from another. Where natural boundaries escaped us, we often defaulted to straight easy-to-understand lines.

All of it culminates to a simple assertion: WE live here. THEY live there.

Iran is where you'd expect it to be, but with a parenthetical reminder that it might also be called Persia. Korea may be whole on this puzzle, but its since been ideologically and violently cut in half with a line that is 148-miles long and 2.5-miles wide.

My very own Cleveland made the cut for the final map, as did Saigon, Vietnam, even though it no longer exists as such. You will not find Massillon, Ohio, which does still exist. It’s about 50 miles south of where I sit typing this. Massillon was home to one Lamont Douglas Hill. Like the fictional Ted Lavender in the above excerpt, Lamont was a soldier in the Vietnam War. Unlike Ted Lavender, he was a real person. And if you walk the miles in his hometown, you’ll eventually come upon the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Viaduct. There, a plaque dedicated to Lamont is situated alongside 17 others: one for each of Massillon's sons who died in the effort to remove the pesky line separating North and South Vietnam from our important maps.

You will not find “Ukraine” anywhere amid these 83 pieces.

The long and fraught history of Russia and the Soviet Union and all those ‘stans is beyond me. But when I look at this humble piece of cardboard, when I consider its quiet audacity, when I look through its deceptive politeness, I wonder about Kiev when this puzzle was manufactured, five or six decades ago. I wonder about Kiev five or six decades from now.

Will it still be called Kiev? Will it be in a country called Ukraine? What about Greenland? Or the Gulf of Mexico?

Or Ohio?

We endlessly flex our might over those imaginary lines between us and them, building great walls in an effort to stop anyone who dares to step over them. As this object so aptly demonstrates, however, borders are nothing more than human constructs. Yet we’ve been recklessly slitting one another's throats over them ever since we emerged from the primordial ooze. Since then, the lethality of our weapons in the fights over borders and names has skyrocketed.

The results, however, are less durable than a kids’ cardboard puzzle.

My collection of puzzles currently exceeds 500. Puzzles come in and puzzles go out. After I work a puzzle, I deconstruct it and place it back in the box with a note. This beauty is missing a piece. Yeah, yeah. Who the hell isn’t? it will say, or, This great old puzzle is complete.

Fellow pilgrim, although I'm more than 1,000 words in, I suppose I could have condensed this puzzle note thusly:

This puzzle is born from truth. This puzzle is born from lies. This puzzle is soaked in blood. This puzzle is forged in hate. This puzzle is full of love. Above all, this puzzle reflects humanity.

This puzzle is complete.

Love, Erin

Follow Erin O’Brien on BlueSky

Pretty brilliant.

I love how you bring all these elements together - the O'Brien story, the puzzle, our world today.

(I too think that The Things They Carried is one of the most amazing stories of all time.)

Every now and then, I stop by Terrapin Cafe, which has a large map of the US on the wall. A strange thing about this particular map is that the time zones are divided by bold lines compared to the state borders.

It fascinates me because those lines are not "fought" for. Except in weird little circumstances like how Gary Indiana is included in the Chicago time zone (Central Standard Time), but the rest of the state is in the Eastern Standard Time along with Ohio, New York and most of the east coast of the US.

What smoke filled room made that decision? Who "fought" for that line and why?

There are many, many distinctions like that on this map and on this map those borders are highlighted by thick black lines. The us and them on each side of each line is both insignificant in importance and profound at the same time.

Thanks for your beautiful article. Very thought provoking.